Aging refers to the continuous and slow decline of biological functions in our bodies over time–functions that are necessary for survival, growth, and fertility.

As men age, there are telltale signs of the aging process. These start in the 30s, and appear around:

Maintaining muscle mass and strength

Bone mass

Red blood cell production

Male hair pattern

Libido and potency

Spermatogenesis (sperm production)

The process of aging in women follows a similar pattern, along with significant changes in female hormones.

More from our health blogs:

All About Testosterone – learn all about testosterone

Normal TSH Levels – what’s healthy thyroid and why?

All About Vitamin D – review of symptoms and impact

The skin starts to wrinkle, muscle strength reduces, vital body functions erode, and quality of life suffers with aging. The most common changes men report in their bodies as signs of aging include:

Lower Strength

Frailty and disability

Sexual dysfunction

Cognitive dysfunction

Reduced vitality, well-being, and quality of life

Prostate enlargement

Cardiovascular health (heart functioning) concerns

Others (lower priority) e.g., fractures

Research on the process of aging is in early stages, however, there are mainly two schools of thoughts.

First one believes aging is part of the natural selection process: once an animal completes reproduction and raises the offspring, it can die. In essence, it has served its purpose in survival of the species.

In contrast, followers of second theory believe in a genetic component. By altering it and adapting to their environments, they believe it is possible to slow down the process.

Considering the slow decline in daily functions, it is natural that people look for possible signs and triggers of the aging process. They desire to monitor and act on them to counter the whole process. Many believe one such sign is the testosterone levels in men.

However, a recent research study that followed 7,671 men and women for 14 years during the Framingham Heart Study did not find any independent correlation of low testosterone to heart disease or heart failure.

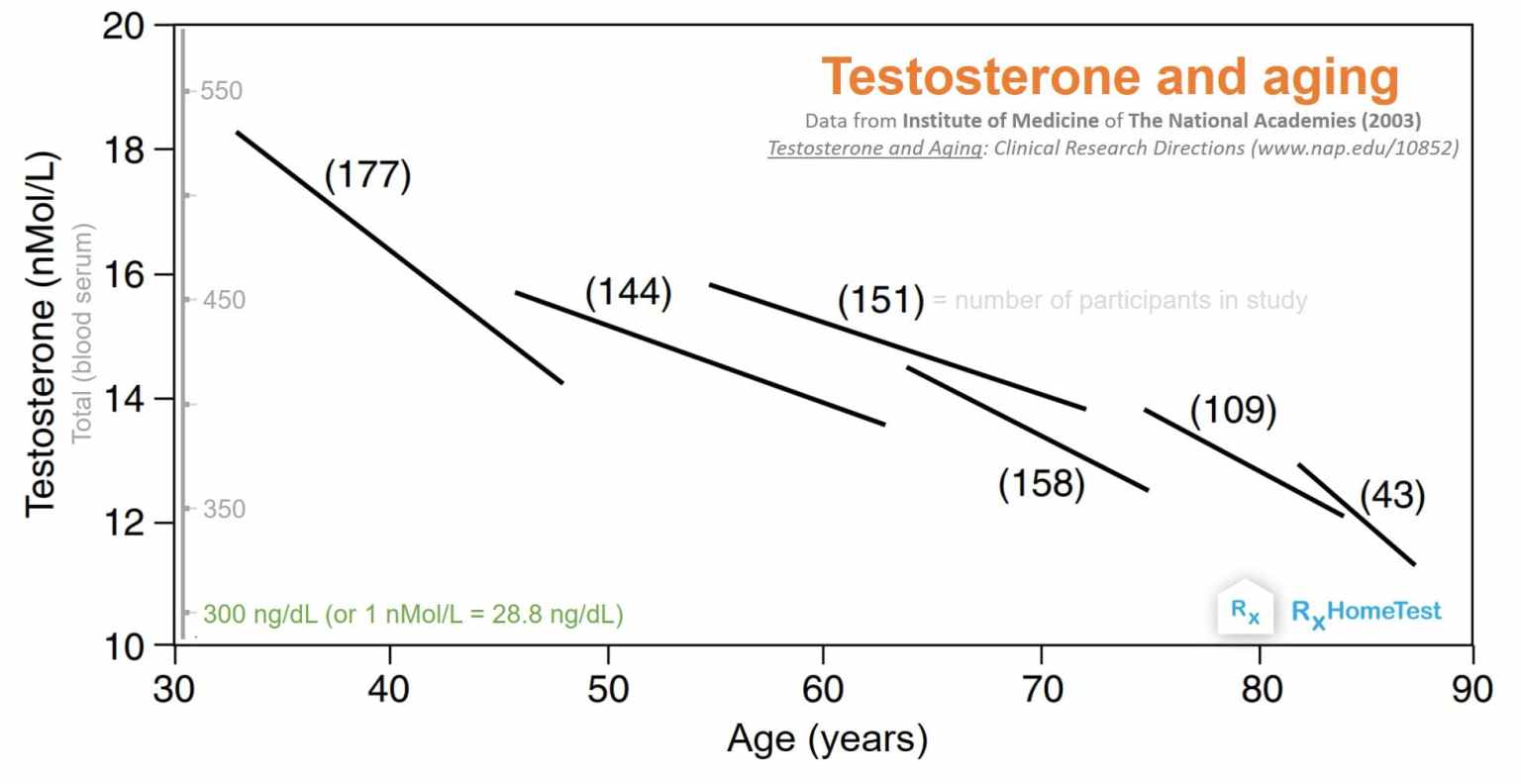

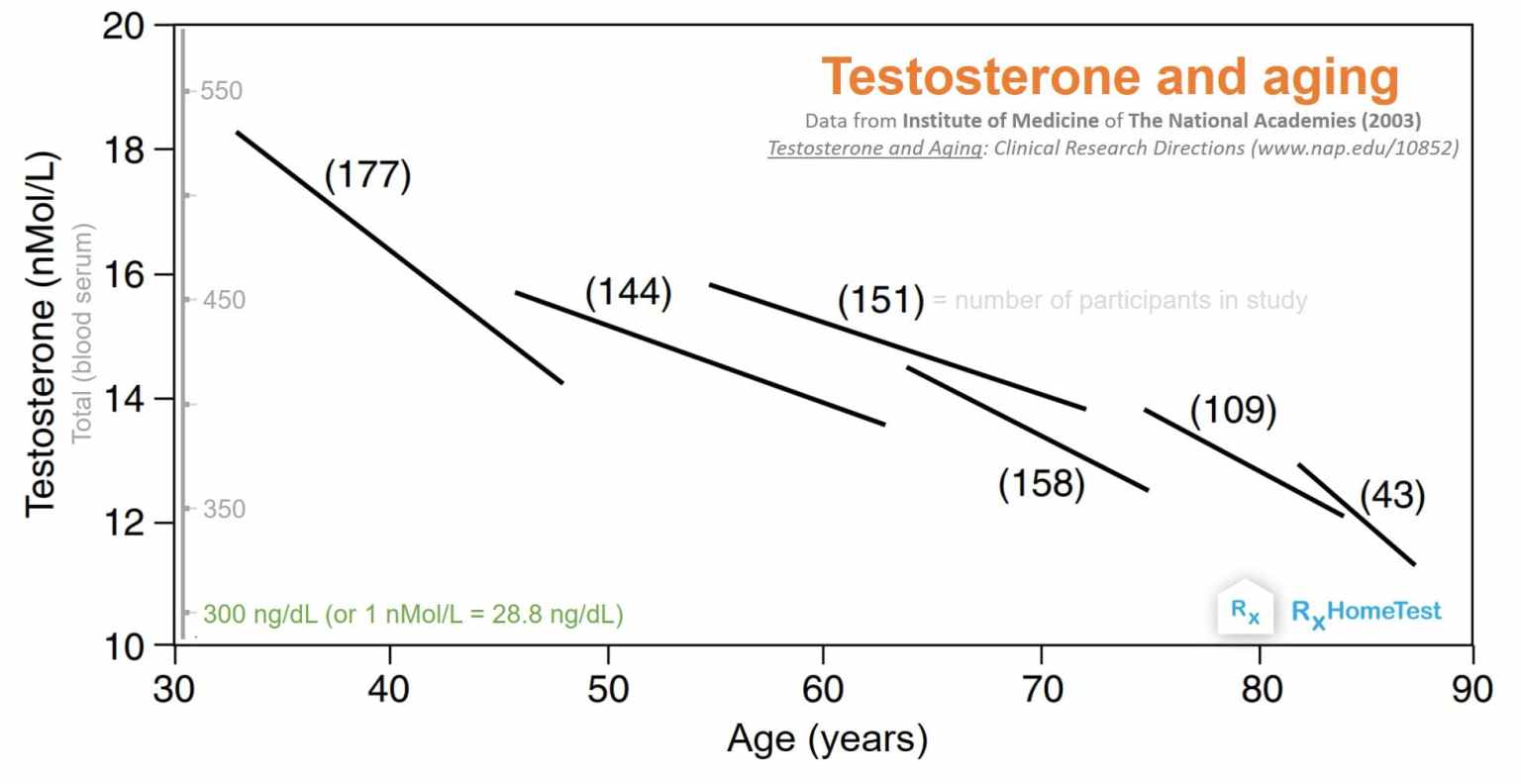

The total testosterone levels continuously decline with age, after peaking in mid-twenties. The plot below, from the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, shows this drop in different age groups from several scientific studies. The number of people in each study is marked next to each line.

Many popular terms describe the gradual decline of hormones in men including adrenopause, somatopause, and andropause. Along with T, this includes DHEA (de-hydro-epi-andro-sterone), DHEAS (DHEA-sulfate), and GH (growth hormone). However, this declining behavior is true for many other physiological processes in the body, not just hormones.

The medical term for low testosterone is hypogonadism.

(Data from National Academies, each line is an independent study showing number of participants.)

The next obvious question is the relationship between age and hormones. Does aging result from low levels? Or, this decline is simply a symptom of getting old?

Data from people using supplements for low testosterone suggest some of these symptoms of aging do improve. However, that’s not always true and generalization is difficult. The research in this field has not conclusively confirmed improvement in symptoms for everyone, however, those with artificially low testosterone levels seem to benefit the most.

In recent years, home based low testosterone saliva tests are gaining popularity. It is recommended that one should understand the available scientific knowledge in order to benefit from them. Hopefully this article, along with summary of scientific research covering all about testosterone will help.

Here we review several scientific studies and try to answer basic questions of how testosterone levels change throughout a man’s life span. We also look at the challenges in measuring testosterone despite a clear dependence on age. Finally, a discussion around the guidelines from FDA and future opportunities for researchers and medical providers follows.

Historically, men considered testosterone as the ‘youth’ hormone. Over hundred years ago, at the time of almost no medical regulation, several people claimed unbelievable health benefits by using testosterone (via self-injections with animal samples).

A recent book by anthropologist Katrina Karkazis and socio-medical scientist Rebecca Jordan-Young explains some of these interesting historical stories and the science behind them.

Things started to change around WWII when Ruzicka and Butenandt independently isolated and synthesized testosterone. Both received the Nobel prize for their achievements in 1939.

Soon, research in this field exploded and first medical product for human use became available in 1950s. However, an oral pill never successfully commercialized since testosterone is weakly soluble in water and difficult to absorb. And the liver rapidly digests it resulting in liver damage.

The focus then shifted to other forms: gels, skin patches, injections, nasal sprays, or gum patches. However, none of them so far have delivered a product that’s safe, effective, and inexpensive. Most still aren’t easy to use or even non-irritant. The search for a product with minimal side-effects, which can deliver doses for prolonged periods, continues.

Due to the ever increasing interest in testosterone, in 1992, the FDA, NIH, and WHO decided to postulate guidelines for a testosterone patch that could be safely used for those with clinically low levels. However, the patches were found to be skin irritant and a better solution was required.

Injections of testosterone in oil suspension were also approved but levels fluctuate significantly from beginning till end. The inconvenience of self-injection or doctor visits limited their adoption.

In 2000, first testosterone gels appeared in the market. These could be easily utilized, however, the constant worry of affecting those coming in contact still remained a problem.

In 2014, the first FDA approved nasal spray for testosterone appeared in market.

Today, over a hundred products including testosterone boosters–supplements that claim to naturally boost the body’s ability to produce testosterone–are available in market.

The average testosterone levels in men vary throughout life. They play a crucial role in the health and development of the human male from conception to well into the old age.

Key changes in testosterone levels in the life cycle of males are:

Source: Age, Disease, and Changing Sex Hormone Levels in Middle-Aged Men: Results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study by Gray et. al. in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Vol 73 (5), 1 November 1991, Pages 1016–1025.

In the seventh week of pregnancy, testosterone production starts in male embryo and the levels remain high until pregnancy for fetal development and normal differentiation of male infants

The levels drop before birth and remain comparable in male and female babies at pregnancy

Right after birth, the levels rise for the first 3 months in boys and then decrease and stay low for years until puberty

During puberty, the levels rise in order to develop secondary male characteristics, sexual behavior and function, as well as sperm production

By the age of 17, total testosterone levels in the blood plasma rise to levels of 300 – 1000 ng/dL (or 10 – 35 nmol/L) based on data collected by Griffin and Wilson (2001) and Merck (2003)

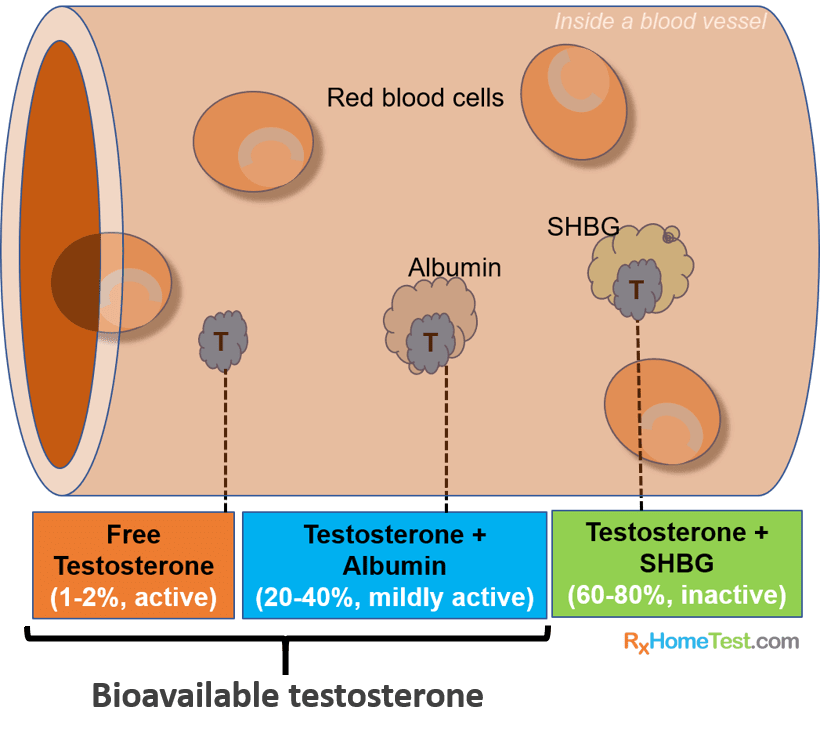

The bioavailable testosterone levels in men remain that high until their 30s and 40s, then drop at a rate of about 1.2% per year as shown by data from Griffin and Wilson (2001) and Harman (2001) (2001); the decrease in total testosterone is slower because the binding protein (SHBG) increase with age by approximately 0.4% per year

Data collected from various studies (plot at the top) show the testosterone levels keep dropping through out the life

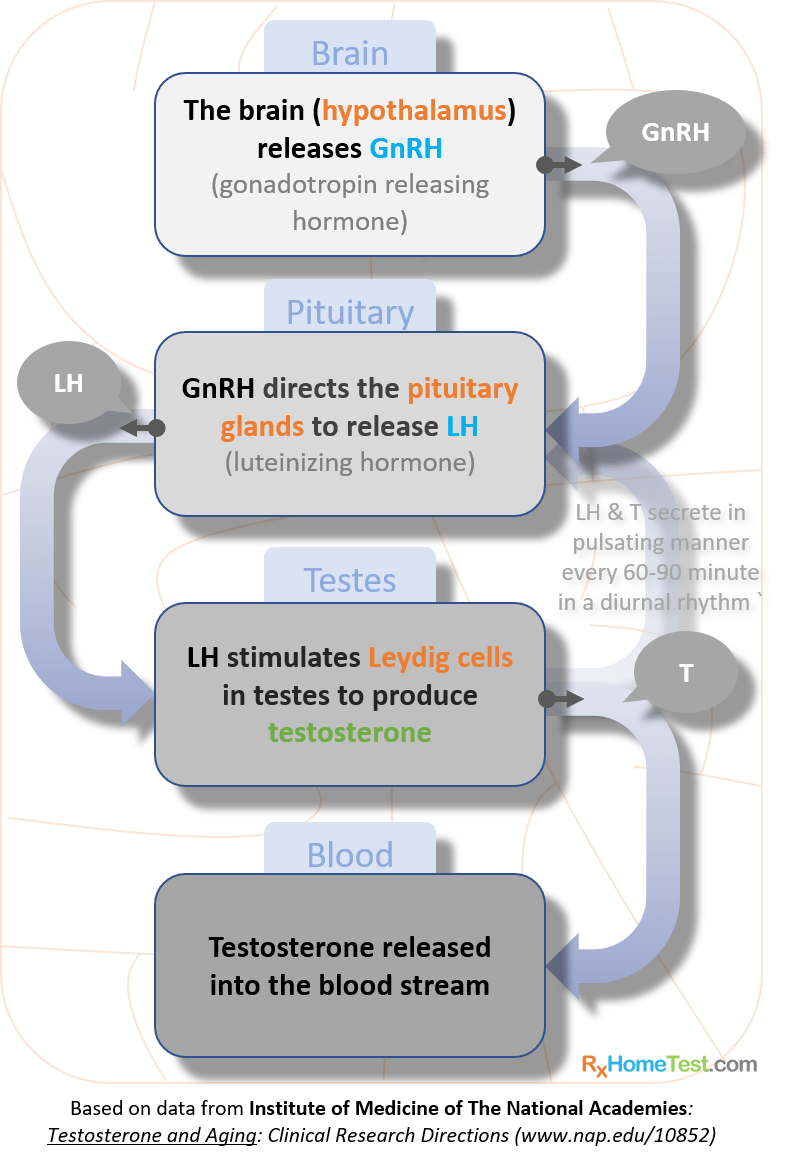

The Leydig cells in testes produce most of testosterone in men. A small amount is also produced in the adrenal cortex (the surface of adrenal glands that releases other hormones including cortisol).

There are four key players in the production of testosterone as displayed in the graph below:

Source: Testosterone and Aging: Clinical Research Directions (2004) – Consensus Study Report by Institute of Medicine of The National Academies.

As a first step, hypothalamus in the brain releases GnRH (gonadotropin releasing hormone).

The GnRH stimulates pituitary glands to release LH (luteinizing hormone) and FSH (follicle producing hormone).

In men, the LH directs Leydig cells to produce testosterone; the FSH stimulates production of sperms in the Sertoli cells.

Research suggests approximately 5-6 mg of new testosterone is available daily into the blood stream of an adult male.

LH and testosterone levels pulsate every 60-90 minutes. A close-loop maintains the diurnal rhythm starting with GnRH release by hypothalamus to final testosterone release into the blood stream.

Several factors related to age affect the lower levels in older men:

A gradual decline of testosterone production in testes and GnRH production in the hypothalamus.

Slow metabolism of the circulating testosterone in blood results in less production by the glands.

The levels have a strong influence from body mass index (BMI = weight/height*height), waist to hip ratio, alcohol consumption, smoking, caffeine intake, and the time of sample collection. Several studies have consistently shown high BMI and abdominal mass related to lower testosterone in older men (e.g., this excellent review by the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies.).

However, the decline is gradual unlike the rapid decline of estrogen in women after menopause.

Testosterone production in our body is a complex biological cycle that involves five key steps–and multiple enzymatic reactions–to convert cholesterol into testosterone as the final product. The plasma cholesterol first converts to pregnenolone, and subsequently into progesterone and DHEA, then androstenediol and androstenedione, and finally testosterone.

The enzyme 5-alpha reductase converts some of the testosterone into DHT (dihydrotestosterone) in prostate, skin, and reproductive tissue. Rest of it converts to estrogen in the fat cells and liver. Therefore, in older men, an increase in fat cells might result in higher estrogen conversion.

As the sketch of a blood vessel above shows, only 1-2% of testosterone circulating in the blood is active, free testosterone.

The rest binds to albumin (60%) and SHBG (sex hormone binding globulin; approx. 40%). The albumin part binds weakly and can rapidly dissociate whenever needed. Therefore, together with free testosterone, approximately 42% is available in the body as bio-available testosterone.

Because SHBG increases with age, the ratio of remaining free testosterone decreases in older men.

Similar to cortisol, testosterone levels follow a 24-hour diurnal rhythm, albeit less pronounced. Levels are highest around after 30 minutes of waking up, and then drop throughout the day. The circadian pattern appears less pronounced in older men (Bremmer 1983, Tenover 1998).

In general, levels can vary significantly from person to person and key variables including age, alcohol consumption, smoking, BMI, and exercise need careful review during testing.

A blood or a saliva sample can measure testosterone levels.

The traditional method with blood serum measures

total testosterone (protein bound plus free)

free testosterone (not bound to protein), and

bio-available testosterone (albumin bound plus free).

However different methods are necessary for measuring each of them:

Total testosterone measurement using radio-immuno-assay is a widely popular method. However, because SHBG–which binds significant portion of testosterone–increases with age. Therefore, in older adults, a higher percentage of testosterone may not available to the tissues making a blood test measurement less useful for older population.

To measure bio-available levels, SHBG is precipitated before measuring the remaining testosterone in serum. Or, one can calculate it by subtracting the SHBG levels from total testosterone. Either way, it has the drawback of inaccurate total testosterone in older population due to age dependence of SHBG levels.

Free testosterone levels are available after calculations from measurement of total testosterone, SHBG, and albumin. Or once can measure it directly by somewhat more expensive equilibrium dialysis methods or immuno-assays.

Saliva testing of testosterone offers ease of sample collection without the need of a medical professional. As the accuracy of testing improves, it has recently become a popular method. Saliva immuno-assay (or ELISA) can be easily standardized and validated with high reproducibility.

The method has become popular due to multiple reasons:

Only unbound, free testosterone is able to diffuse through cells. Therefore, a saliva test will only measure free testosterone.

There is no interference from binding proteins and no mathematical estimation is necessary.

The ability to collect multiple samples without requiring a health professional in the field makes it a superior choice in testing.

It’s a non-invasive, stress-free process–important factor for children and those afraid of needles.

Because testosterone levels fluctuate throughout the day, it allows the ability to collect multiple samples as necessary.

A CLIA certified lab with well established references is best way to test free testosterone. However, a general lack of awareness among healthcare professionals about the accuracy, reproducibility, and validity has made this method less popular.

For diagnosis of hypogonadism, one should follow the following steps:

A low testosterone test as a first step (using sample collected in the early morning).

A comprehensive history and physical exam if one believes they do not have normal testosterone levels.

A second lab test from sample collected in the morning.

The diagnosis can be tricky as low levels may be marker of ill health (not a cause of it). And:

There are still no clear guidelines of what levels are deficient

There is uncertainty regarding which measure of T is appropriate (total, free, or bioavailable?)

Data from several scientific studies suggest the following general testing guideline:

For those over 50, AACE (American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists), the guidelines (from 2002) recommend:

* Total T <= 200 ng/dL: hypogonadism is confirmed unless serious pituitary and hypothalamic issues

* Total T between 200 and 400 ng/dL: further testing and consideration for therapy

* Total T > 400 ng/dL: no deficiency

Other studies suggest deficiency in older men at 2-std dev from normal levels of testosterone in young men (Heaton, 2003):

* Total T < 320 ng/dL

* Free T < 7 ng/dL

* Bioavailable T: 90 – 230 ng/dL

For our home testosterone test kits from saliva samples, we define a free testosterone value below 5 ng/dL (50 pg/mL on the report) as low and recommend further attention and changes in lifestyle.

Those below 1 ng/dL (10 ng/dL on the report) should test again with a different sample and talk to their primary physician.

The FDA explicitly recommends use of prescription only in certain medical conditions. Hypogonadism (unusually low testosterone levels) is a medical condition resulting from inadequate gonadal function, a deficiency in sperm production, and gonadal hormone secretion. Depending on the cause, it is classified into two types:

Primary hypogonadism: when testes do not function properly due to surgery, radiation, genetic and developmental disorders, infection, or liver and kidney diseases. In a genetic disorder—Klinefelter’s syndrome—where an extra sex chromosome XXY is present. Primary hypogonadism results in low testosterone, but high FSH and LH levels.

Secondary hypogonadism (also called hypogonadotropic): results from disorder of pituitary gland or hypothalamus. Causes include pituitary tumors, surgery, radiation, infections, inflammation, trauma, bleeding, genetic problems, nutritional deficiency, iron excess. Secondary hypogonadism results in low testosterone, and low to low-normal FSH and LH levels.

The FDA has recognized abuse of testosterone products and has provided guidelines for approval and prescription of testosterone products.

In summary:

Only to be prescribed for men who have low levels of testosterone caused by certain medical conditions (e.g., problems with pituitary glands, hypothalamus in brain, damage to testicles)

FDA explicitly says that the ‘benefit and safety of these medications have not been established for the treatment of low testosterone levels due to aging, even if a man’s symptoms seem related to low testosterone’

Some studies have indicated increased cardiovascular risk associated with testosterone use, including aging men taking testosterone. Some studies reported an increased risk of heart attack, stroke, or death associated with low testosterone treatment, while others did not

The diagnosis of clinically low testosterone, or hypogonadism, requires two separate lab tests as evidence (and samples collected in the morning)

Testosterone is a Schedule III controlled drug due to abuse potential; each refill may need to have a new prescription

Based on available data, the FDA says those taking therapy are at higher risk of stroke and heart attack like symptoms and should monitor them carefully:

Chest pain

Shortness of breath and trouble breathing

Weakness in one part or one side of body

Slurred speech

Data from US Census Bureau projects the ratio of older population will keep increasing in foreseeable future. The plot below shows US population projections for 2018 and 2030.

The orange region in this plot forecasts a 15% increase in population of those 30 years and older by 2030. That’s approximately 15 million more men with declining testosterone levels and searching for answers regarding their health outcomes.

That is a strong motivation for scientists, researchers, and medical providers to find better answers. For those serving this market segment, the opportunities are enormous.

The Wired Magazine’s perspective on T. (15 minute read that goes through brief history, how middle aged men are going after testosterone therapy, and how the industry is trying to advertise the benefits although scientific data are scarce).

Aging: the biology of senescence, a chapter from Developmental Biology, 6th Ed. (excellent 15 minute read on causes of aging, types, and snapshot summary of the field)

Testosterone: An Unauthorized Biography by Rebecca M. Jordan-Young, Katrina Karkazis Harvard University Press (2019).

FDA’s official webpage on testosterone (short summary of the testosterone as a drug, guidelines for users and prescribers, and links to key studies in the field).

Testosterone and Aging: Clinical Research Directions (2003) (studies reviewed by a committee of experts in the field assembled by the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies).

Drugwatch.com’s superb review of testosterone therapy: (an comprehensive and authoritative review on the background and scientific literature of testosterone, a must read for those interested to know more).